The Fate and Legacy of the GU272

A fateful bargain

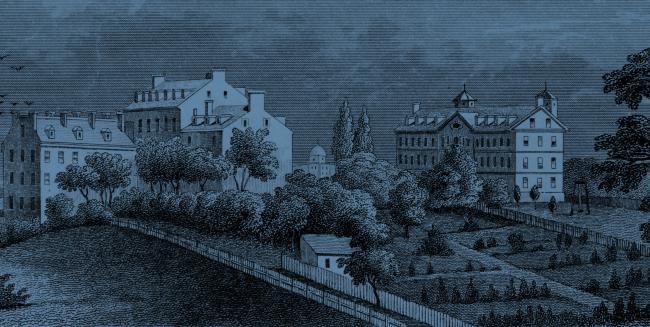

In the summer of 1838, Georgetown’s Jesuit priests made a fateful bargain. Debts were mounting from the construction and maintenance of Georgetown College, and an infusion of cash was urgently needed. At the time, the Jesuits’ most valuable assets were the hundreds of slaves who worked their local tobacco plantations.

Financial Needs

The slaves were themselves Catholics, many having been baptized by Father Thomas Mulledy, President of Georgetown from 1829 to 1837, or his successor, Father William McSherry.

Nevertheless, the two men concluded in 1838 that selling most of the college’s slaves was both expedient and necessary. In addition to having concerns about the college’s pressing financial needs, the Jesuits may have calculated that the cost of owning slaves was more expensive than paid labor. They were also likely aware that public sentiment in the District of Columbia was beginning to shift against slavery.

On June 19, 1838, the Jesuits signed a contract with Louisiana sugar plantation owners Jesse Batey and Henry Johnson (a congressman from Louisiana, who had previously served his state as a governor and U.S. senator), sealing the fate of approximately 272 men, women, and children—and altering the lives of generations of their descendants.

One of the largest sales of human beings in US history

The selling of the GU272 raised $115,000, equivalent to about $3.3 million today, enough to allow the Jesuits to pay off their most pressing debts and eventually transform a modest college into prestigious Georgetown University.

Determining the fate of the individuals who were sold has often been challenging, due to a lack of records, imprecise documentation, and name changes. Although the slaves sold by Georgetown in 1838 collectively came to be known as the GU272, to date researchers have documented 206 sent to Louisiana and 108 who were part of the original sale but remained in Maryland or were sold elsewhere.

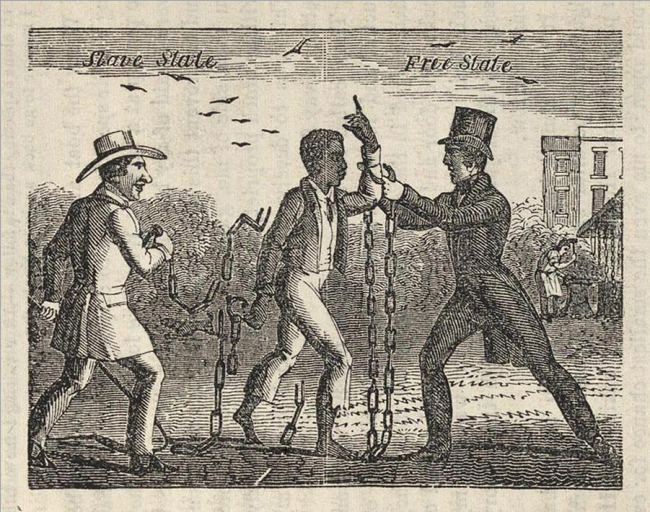

Some people in this latter group, known as the “Lost Jesuit Slaves,” avoided transport by escaping or because of an existing marriage. (A Georgetown slave married to a slave on a neighboring plantation—or to a free person of color—couldn’t be separated from a spouse, according to the Jesuit Superior General in Rome.)

Bound for Louisiana

The largest group of slaves bound for Louisiana was rounded up in early November 1838, and sent to Alexandria, Virginia, to be loaded onto an ocean-going vessel chartered expressly for the purpose. The Katherine Jackson, which transported most of the slaves, departed Alexandria on November 13 and arrived in New Orleans on December 6, 1838.

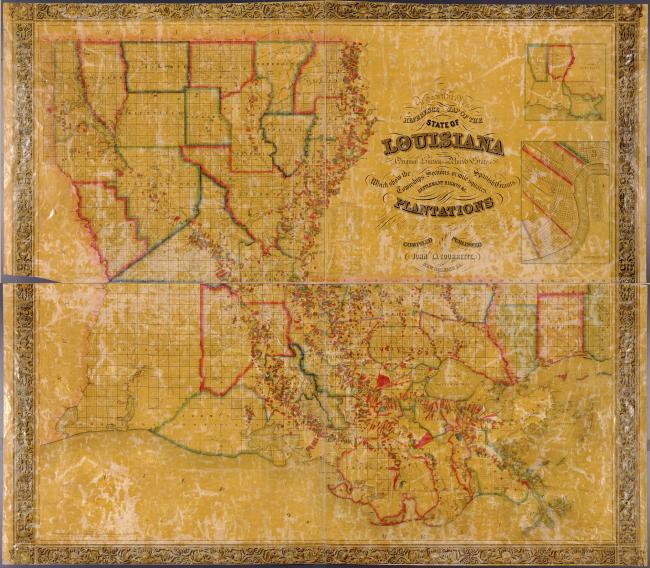

After arriving in Louisiana, these slaves were split among three locations in the vicinity of Baton Rouge. West Oak Plantation in Iberville Parish on the Bayou Maringouin was owned by Jesse Batey. A nearby plantation in Maringouin was owned by Henry Johnson, as was Ascension Plantation (later known as Chatham Plantation) in Ascension Parish near Donaldsonville. In all, approximately ninety Georgetown slaves were initially transplanted to Maringouin—a place so infamous for heavy infestations of mosquitoes that its name is the Cajun French word for the insect. Many descendants of the GU272 still live in Maringouin and adjacent communities.

"No one does this but bad people..."

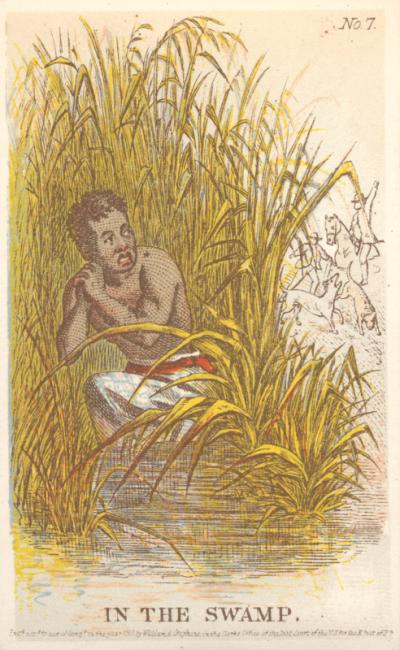

Even among those who supported or were indifferent to slavery, the life of a field slave in the Deep South was regarded as an exceptionally cruel fate. Only the West Indies, where more than half of all slaves died before reaching age forty, had a worse reputation.

On sugar cane plantations like those owned by Batey and Johnson, work consumed six days a week, from sunrise to sunset. Typically, field slaves were crowded into small, hot dirt-floor shacks, fed meager diets, and were generally subject to extreme brutality at the whim of white overseers. Northerners and foreign visitors to the South expressed shock at how frequently—and with what viciousness—slaves were whipped or physically abused. Female slaves of all ages were subject to sexual abuse. As soon as they could conceive, young girls could be chosen as “breeders,” and forced to bear children to be sold to other plantations, a practice that generated enormous wealth for their owners. Any slave caught attempting to escape would be severely punished, often permanently maimed or killed outright.

Accounts of Southern barbarity were common in newspapers and broadsides of the time; the Jesuits would have known the likely fate of their fellow Catholics. A few priests expressed qualms about the morality of human trafficking to Jesuit authorities, although most were concerned with the threat a heavily Protestant South would undoubtedly present to the slaves’ Catholic faith. Writing to the Jesuit Superior General from his home in Newtown, Maryland, on October 20, 1838, Father Peter Havermans lamented the loss of the slaves, noting that news of the sale had provoked negative reactions locally.

"...Nevertheless about an especially important thing, about the slaves of course, who all as I was then anticipating, have been sold, I will not now say much. When I consider the affair as now it has been brought to an end and after the fact, I will say only so much, that, inasmuch as I am able to apprehend, they were sold to infidels, living in places of infidelity, at a distance of five thousand English miles. The affair gave many here a reason for speaking badly about us. No one does this but bad people, as they are dealers of Negroes, who care for nothing except money, or also by those who by necessity, e.g. from misfortunate, or of paying contracted debts, are driven toward it. Others (even Protestants) consider this forbidden. And I also will say that this thing was especially grim and displeasing to me, and still is, even more because the slaves who were under my care conducted themselves well, and, as long as they were beneath me, they were of great use for the Society, and would have been of greater use still, and for the rest, if they did need to be sold, they could have been sold without scandal and clear danger of losing their souls..."

Father Peter Havermans, October 20, 1838

Although the money raised by the sale secured financial stability for Georgetown College, the Jesuits experienced a backlash of sorts from the negative publicity the sale generated. The same year, Father Mulledy was recalled to Rome, and in 1839 Pope Gregory XVI barred Catholics from engaging in the business of slavery. Private ownership of slaves, and private sales, however, were not specifically forbidden.

As for the reactions of the GU272 to their fate, Father Havermans described attitudes that ranged from stoic to desperate. In a November 12, 1838 letter, he recounted the pleas of one pregnant woman:

"The slaves with heroic fortitude were giving themselves to fate and with Christian resignation relinquishing themselves to God. One woman more pious than the others, and at that time pregnant most demanded my compassion. She was coming toward me so that for the last time she could greet me and seek benediction, and she observed as she was genuflecting: “If ever someone should have reason for despair, do I not now have it? I do not know on what day the birth will come, whether on the road or sea. What will become of me? Why do I deserve this?” I was saying “Trust in God.” So it was, she agreed, I offered myself totally to her. All were coming to me seeking rosaries, medals, a cross or something so that they would remember me. And with how much obedience they went to the boat. Only one tried to run away. And the official was not compelled to bind him...

The ... encumbered slaves remain here so that either their wives or husbands might be bought, or there might be an arrangement concerning them by said [Henry] Johnson. For I wish that he would not separate them from their partners and children..."

A neglected people

Approval of the 1838 slave sale was granted subject to several express conditions, including that families not be separated and that the slaves be permitted the free exercise of their Catholic religion in Louisiana. According to present-day historians at Georgetown University, none of those conditions were fully met.

In letters written to Jesuit superiors in Maryland, one priest who accidentally crossed paths with the slaves in Louisiana after the sale bemoaned the fact that the slaves couldn’t practice Catholicism. After a trip to Louisiana in 1848, Father James Van de Velde wrote to Father Mulledy—who by that time had been reinstated as president of Georgetown—and asked him to pay to build a church to “provide for the salvation of those poor people, who are now utterly neglected.”

Van de Velde reported that many of the slaves were given no time to attend Mass, were not being baptized, and were “without any religious instruction whatever.” No evidence suggests that the Maryland Jesuits ever provided the funds requested.

Emancipation and beyond

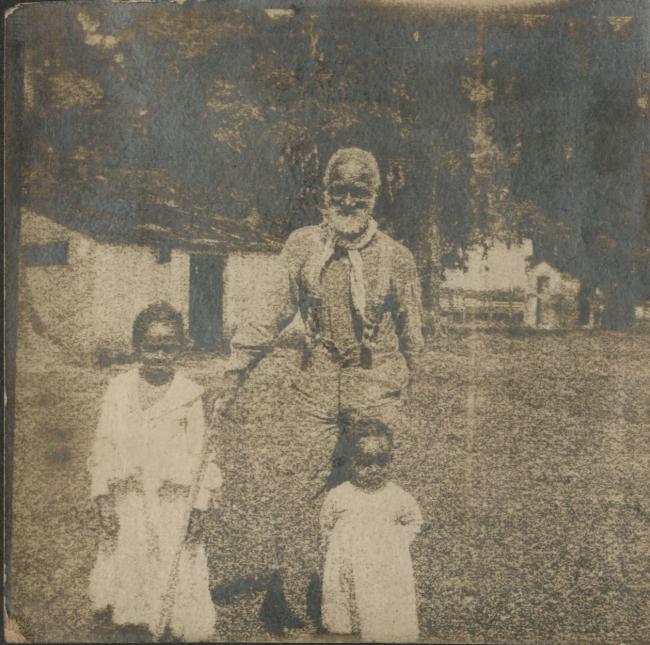

More than twenty-five years after the sale to Johnson and Batey, the approximately eighty Georgetown slaves who survived the Civil War were emancipated (both legally and practically) when that conflict came to an end on April 9, 1865.

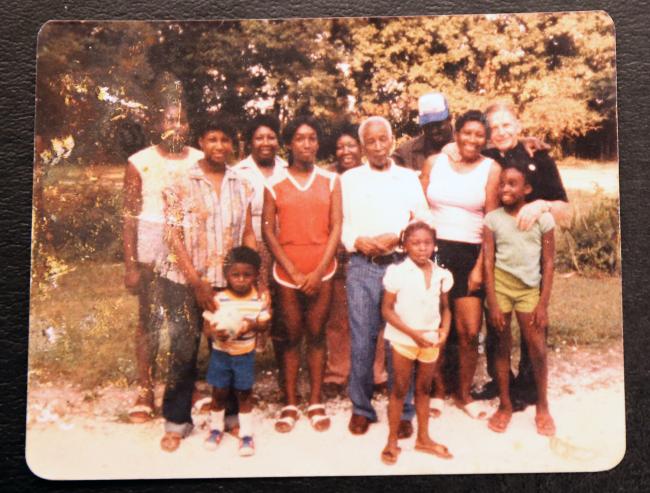

Yet many African-Americans continued to live in conditions similar to slavery, exacerbated by postbellum poverty and later by Jim Crow laws enforcing racial segregation. In later years, from approximately 1916 to 1970, GU272 descendants were among the six million African-Americans who left the South in search of better lives in other parts of the country. Today, GU272 descendants live across the United States.

The sale of the GU272 was never a secret at Georgetown—or anywhere else. The transaction was documented in original letters and materials kept in the college archives (and more recently in academic articles and books published by scholars and even a few Jesuits). Nevertheless, the history of Jesuit slaveholding failed to penetrate the consciousness of most members of the Georgetown community in the modern era. Whispers, rumors, half-truths, and ignorance abounded.

In 2015, one highly-regarded Georgetown figure acknowledged that the University sold slaves to Louisiana in 1838, but erroneously declared that all of them had quickly died of a fever upon reaching their destination. Generations of Georgetown faculty and students were oblivious to the fact that two prominent campus buildings were named for the Jesuit priests (Mulledy and McSherry) who were most responsible for the sale.

Uncovering the truth

In fall 2015, in the wake of Harvard, Columbia, Brown, and other universities admitting their past involvement in slavery, students at Georgetown began demanding to know the truth about rumors heard on their campus. The university established a working group to investigate the matter but student demonstrations that fall lent the efforts urgency, as did the formation of the independent nonprofit Georgetown Memory Project (GeorgetownMemoryProject.org).

The project was formed by a group of alumni led by Richard Cellini, a Massachusetts lawyer and entrepreneur in the tech industry. Cellini raised money to hire a team of genealogists to trace descendants of the Georgetown slaves. Adam Rothman, an historian and a member of the university’s working group, began combing through the college archives looking for pre-sale references to the GU272.

Finding the GU272

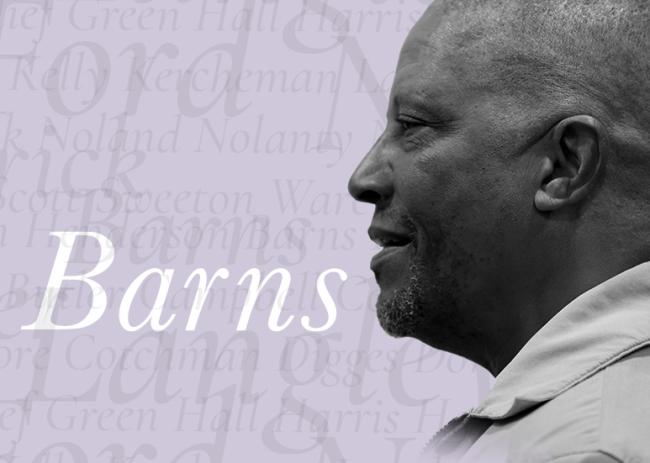

This information helped lay the groundwork for Cellini, Judy Riffel (lead genealogist for the Georgetown Memory Project), and others working with them to trace more than 200 of the slaves and over 7,700 descendants (living and deceased)—more than 4,000 of whom are alive today. Upon learning about their connections to the GU272, many descendants have undertaken their own significant genealogical research.

On April 18, 2017, Georgetown University and the Society of Jesus’s Maryland Province apologized for their roles in the 1838 sale of slaves. More than 100 descendants attended the ceremony. Georgetown’s Mulledy Hall was renamed to honor Isaac Hawkins, the first person listed in the 1838 sale agreement. The McSherry building was renamed for Anne Marie Becraft, a free woman of color who established a school for Black girls in the town of Georgetown in the nineteenth century.

Much more work remains to be done. Using a statistical model developed by a scientist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Richard Cellini estimated that the original members of the GU272 have collectively produced 12,000 to 15,000 descendants (living and deceased) since the 1838 sale—more than half of whom are probably alive today.

Notes

Notes

1 Suzanne Monyak, “Built by Slaves and Jesuits,” The Hoya, January 30, 2015

(thehoya.com/slavery).

2 “Articles of Agreement between Thomas F. Mulledy, of Georgetown, District of Columbia, of one part, and Jesse Beatty and Henry Johnson, of the State of Louisiana, of the other part. 19th June 1838. Georgetown Slavery Archive, slaveryarchive.georgetown.edu/items/show/1.

3 Laine Kaplan-Levenson, “Georgetown University Sold 272 Enslaved People to Louisiana: The Descendants Speak (Part I),” WWNO, New Orleans Public Radio, February 9, 2017 (wwno.org/post/georgetown-

university-sold-272-enslaved-people-

louisiana-descendants-speak-part-i).

4 “Articles of Agreement” [note 2].

5 “The Lost Jesuit Slaves of Maryland: Searching for 91 people left behind in 1838,” GeorgetownMemoryProject.org/

wp-content/uploads/Research-Memo-

Lost-Jesuit-Slaves.pdf, page 9. Also, Terrence McCoy, “They thought Georgetown University’s missing slaves were ‘lost.’ The truth was closer to home than anyone knew,” The Washington Post, April 28, 2018 (washingtonpost.com/local/social-issues/they-thought-georgetowns-missing-

slaves-were-lost-the-truth-was-closer-

to-home-than-anyone-knew/2018/04/28/

074beb66-3e65-11e8-a7d1-e4efec6389f0_story.html).

6 The manifest of the Katherine Jackson, which transported some of the slaves from Georgetown to Alexandra and then to New Orleans can be seen at the Georgetown Slavery Archive website, at slaveryarchive.georgetown.edu/items/show/2.

7 See the “Slave Labor” article (slaveryand

remembrance.org/articles/article/

?id=A0056), on Colonial Williamsburg’s Slavery and Remembrance website.

8 Letter from Father Peter Havermans to the Superior General, October 20, 1838, at the Georgetown Slavery Archive, slaveryarchive.georgetown.edu/items/show/226.

9 Ibid., November 12, 1838.

10 Rachel L. Swarns, “272 Slaves Were Sold to Save Georgetown. What Does It Owe Their Descendants?,” The New York Times, April 16, 2016 (nytimes.com/2016/04/17/us/

georgetown-university-search-for-slave-

descendants.html).

11 Letter from Father James Van de Velde to Father Thomas Mulledy, March 28, 1848, at the Georgetown Slavery Archive, slavery

archive.georgetown.edu/items/show/3.

12 Noel King, host, Planet Money: Episode 766: Georgetown, Louisiana, Part One (npr.org/templates/transcript/transcript.php?storyId=525058118).

13 Katherine Shaver, “Georgetown University to rename two buildings that reflect school’s ties to slavery,” The Washington Post, November 15, 2015 (washingtonpost.com/local/georgetown-university-to-rename-two-buildings-that-reflect-schools-ties-to-slavery/2015/11/15/e36edd32-8bb7-11e5-acff-673ae92ddd2b_story.html).

14 As of December 1, 2018, 214 original GU 272 members and 7,699 descendants had been identified and located by the Georgetown Memory Project. GeorgetownMemoryProject.org homepage.

15 “Georgetown Apologizes for 1838 Sale of 272 Slaves, Dedicates Buildings,” at georgetown.edu/news/liturgy-remembrance-contrition-hope-slavery.

16 Matthew Quallen, “Beyond the 272 Sold in 1838, Plotting the National Diaspora of Jesuit-Owned Slaves,” The Hoya, April 29, 2016 (features.thehoya.com/beyond-the-272-sold-in-1838-plotting-the-national-diaspora-of-jesuit-owned-slaves).